Haskells: The Life and Death of a Whittle-le-Woods Farm

You would have to be a very long-term resident of

Whittle-le-Woods to remember Haskell’s Farm. Its farmhouse and outbuildings

were demolished in the early 1970s and its farmyard and fields are now covered

by housing. It was a small family farm, little more than a smallholding, one of

hundreds of such farms that covered the rolling hills that

surrounded the east Lancashire textile manufacturing towns throughout the

nineteenth century and into the twentieth. Most are now gone, their fields

absorbed into larger concerns (or built upon) and their buildings torn down or converted into private

houses. In this article I will chart the history of Haskell’s, as an example of

this unsung but important aspect of Lancashire’s agricultural economy.

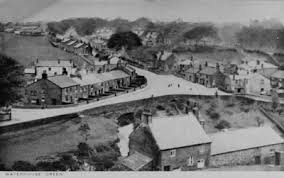

It was called Haskell’s in Kenneth Hodgkinson’s history of Whittle and Clayton-le-Woods, but Haskell’s was not its original name and it did not acquire that designation until the Haskell family took it on in the early twentieth century. Its proper name was Waterhouse Green farm. Its farmyard was situated on a flat piece of land just across the river Lostock from Waterhouse Green, the farmhouse and attached outbuildings snuggled under the steep bank of Dolphin Brow. Its fields were on the top of the bank, between what is now Preston Road (the A6) and Chorley Old Road. The tithe apportionment schedule of 1840 states that it was 10 acres in size, but by 1851 it was just under six acres. Either way, it was a very small farm, but in the nineteenth century, Lancashire had a higher proportion of small farms than almost every other English county. Towards the end of that century, the average farm size in Lancashire was 40 acres, compared with 80 acres for England as a whole and the average for East Lancs was only 30 acres, with many of 10 acres or less.

The Small Farms of

East Lancashire

Haskell’s was not even the smallest farm in

Whittle-le-Woods. In 1851 there were 34 farms in Whittle. The largest were the

home farms of Shaw Hill and Crook Hall, each around 75 acres, followed by

Swansea farm at 52 acres. Only two other farms were over 40 acres and 15, or

44%, were less than 10 acres, the smallest being a mere 3 acres. The average

size of Whittle’s farms was just under 20 acres (see Table One below).

Such figures conjure up a stereotype of poor, uncouth

peasants scratching out a subsistence existence from straggly crops and

sore-infested animals while living in damp and draughty hovels. This was indeed

the view of some contemporary commentators. R. W. Dickson wrote in 1815 about

Lancashire’s small farmers, “Men of this stamp are quite unfit for the

management of land and besides they have neither the capital or knowledge

necessary for rendering the land productive and beneficial” and in 1851 J.

Caird was still complaining that “Unfortunately, the great proportion of

[Lancashire] is held by small farmers who, however industrious, do not possess

the intelligence or capital requisite to meet the natural difficulties”. The

implication was that the rental income that gentleman landowners could expect to

gather from such farmers was limited by their country bumpkin-ness. However,

more recent research has shown that, far from being backward and fit only to

meet their occupants’ meagre needs, east Lancashire’s small farms were thriving

small businesses that played an important role in providing produce for its

growing industrial towns.

A paper by Michael Winstanley of Lancaster University, published

in 1996, offers a positive view of these farms. He points out that, “small-scale

farming was far from confined to the geographical periphery, but was in fact

most heavily concentrated in areas with low indices of "rurality"

close to densely populated urban settlements”. Farms like Haskell’s were

predominantly dairy farms, supplying milk, butter and cheese to those living in

the industrial towns. Small farmers also reared pigs and as the 19th

century wore on, poultry. Many of the farmers retailed their produce directly

to customers, travelling into the towns themselves to sell their wares at

markets. This maximised their returns and as they were family farms, with wives

and children working in the fields and milking sheds, they saved on labour

costs. Rather than peasants, Winstanley suggested that east Lancashire’s small

farmers should be regarded as petit

bourgeoisie. Winstanley also showed that when the nationwide agricultural

depression took root in the late 19th century, Lancashire’s small

farms weathered the economic downturn better than larger, less flexible and

adaptable concerns.

From Waterhouse Green

Farm to Haskell’s Farm

We cannot date the foundation of Waterhouse Green

(Haskell’s) farm precisely, but we can make an educated guess. Some of

Whittle’s farmhouses date from the 17th century and probably

replaced earlier buildings, but there was an expansion of small farms in the

late 18th and early 19th century. This was due to the

growth of the population of Lancashire, leading to increased demand for

farmland and for accommodation for those who wanted to farm. Marginal land was

turned to farming and some farms were sub-divided or sub-let. Some of Whittle’s

farms listed in Table One have more than one family as farmers and some family

names occur more than once, offering evidence for this sub-division.

It is most likely that Waterhouse Farm began as a separate

holding during this expansion. The design of the farmhouse reinforces this view.

It is a “laithe house”, a design common among northern farms of this period. A

decent sized farmhouse has a barn and other outbuildings attached to it in a

line that runs east-west under the bank of land on which the fields sit. It may

be possible to date its foundation more precisely. In 1825, a new turnpike road

was constructed, running from the top of Shaw Brow north to Radburn Brow and

bypassing Chorley Old Road as the main road from Chorley to Preston (this road

is now Preston Road, part of the A6). This led to the isolation of a wedge of

agricultural land between the new turnpike road and Chorley Old Road. It

appears that the southern end of this wedge was enclosed after the road was

built, as field boundaries and ownership within the wedge do not correspond to those

outside it. Waterhouse Green farm is at the southern tip of this wedge, with

originally one outlying field further north. It was in existence as an entity

in 1840, owned by Cordelia Elizabeth Freeman, the proprietrice of the Crook

Hall estate. It was the only land that she owned in that area. This appears to

date the establishment of the farm to between 1825 and 1840.

It is possible that the farm was built on part of th original Choley to Preston turnpike (now Chorley Old Road). Old maps appear to show this road running to the north of the river Lostock prior to the construction of Waterhouse Green Bridge. 19th century odnance survey maps show a path running east from the farmhouse to Chorley Old road - this may be th original path of the turnpike road.

It is possible that the farm was built on part of th original Choley to Preston turnpike (now Chorley Old Road). Old maps appear to show this road running to the north of the river Lostock prior to the construction of Waterhouse Green Bridge. 19th century odnance survey maps show a path running east from the farmhouse to Chorley Old road - this may be th original path of the turnpike road.

In 1840 the farm had four fields. Barn field and Cock field

were pasture, while Slackey Meadow and Hill field were meadow, growing grass

for winter feed. There were just two acres of pasture, barely enough for one or

two cows. By 1851, the outlying Hill field had apparently been given up. Small

farm tenancies tended to be renewed annually, allowing tenants to add or

subtract land according to their needs. For some reason, Hill field remained

undeveloped for many years after the rest of the surrounding land had been

turned to housing, but it is now the site of Paradise Close.

|

| The footpath leading from the Bay Horse on Preston Road up the hill to Chorley Old Road marks the northern boundary of Haskell's farm, after Hill field had been given up |

For much of the nineteenth century, the tenants of Waterhouse Green Farm were the Beardsworth family. In 1840 the farmer was 47 year old John Beardsworth. He had been born in Whittle, his father possibly another John Beardsworth, who died in 1848 aged 80. His wife Alice, who was seven years older than him, was also born in Whittle and they had at least five children. In 1841, four of their adult children lived with them in their relatively spacious farmhouse. Their daughters Mary and Catherine undoubtedly helped on the farm and with taking the produce to market. Sons Edward and James brought in extra income through their employment as labourers.

While small-scale farming was economically viable in east

Lancashire, extra income was always welcome. Some of Whittle’s small farmers

had other jobs, including, in 1851, innkeeper, quarryman, block printer and

cotton manufacturer (overseeing home-based handloom weavers). Others, including

the Beardsworths in later years, took in lodgers. Waterhouse Green farm also

had an orchard, on the flat ground between the river Lostock and the farmhouse.

This was not unusual, the tithe apportionment schedule of 1840 lists no fewer

than nineteen orchards in Whittle, with apples the most likely produce.

Alice Beardsworth died in 1866, aged 82 and John followed

her in 1868. The farm was taken on by their daughter Catherine, assisted by her

younger brother James. This arrangement lasted until James’s death in 1896,

aged 72. In 1901, Catherine, then aged 79 was still farming the land and had

for company a 21-year-old lodger, William Mather, a teacher at the elementary

school on Preston road.

By 1911 Catherine had died and the farmer was 38 year old

George Haskell. He had been born in Portsmouth in 1873, the son of a farmer and

hay and straw dealer and had worked on his family’s farm before moving to

Lancashire to seek his fortune. Such a move was less unusual at that time than

it would be now. Farming in the south of England was in a state of depression,

due to competition from cheap imports, while as we have seen, the thriving

market for produce in the Lancashire mill towns kept the small farms of East

Lancashire busy.

In 1898, George Haskell married Margaret Monk, the daughter

of a Bretherton farmer. By 1911 they had been at Waterhouse Green farm for at

least five years and had four children. Haskell was lucky to secure Waterhouse

Green farm as at that time up to twenty applications could be made for a single

vacant tenancy. Doubtless, the fact that both he and his wife had been brought

up on farms counted in his favour. Ownership of the farm remained with the

Haskell family for the rest of its existence – hence the popular name of

Haskell’s farm.

|

| These fragments of willow pattern crockery, dug up from a garden in Grasmere Grove, may have been discarded from Waterhouse Green farm |

The Demise of Haskell’s Farm

In the 1921 census return, George Haskell was still living in Waterhouse Green Farm, but listed his occupation as a labourer at Lowe Mill Print Works - and out of work. Three of his children were weavers in local mills. Overall, small-scale farming remained viable in East Lancashire for

the first half of the twentieth century, but by the nineteen-sixties small

farms had had their day. At the same time, pressure was growing for land for

new housing. Plans were afoot for a designated “new town” in Central

Lancashire, to embrace the triangle between Preston, Chorley and Leyland.

Owners of small farms were often keen to sell their increasingly unprofitable

land to developers.

In 1968, the owner of Waterhouse farm was J. Haskell,

possibly George’s son James, who would then have been aged 57. His address was

Greenacres Farm, Chorley Old Road (situated by the

junction with Radburn Brow and now a small housing estate). Waterhouse Green farm was described as being used for poultry –

1960s maps show a large square building to the west of the farmhouse that may

have accommodated battery hens.

In the same year, the Preston building firm of Conlon

Brothers applied to Chorley Rural District Council for planning permission to

build a housing estate on the whole of Waterhouse Green farm’s six acre site.

There would be 47 new houses sited on two new cul-de-sac roads, with fourteen

houses on the site of the farmhouse, yard and orchard (Grasmere Grove) and 33

on the fields above (Langdale Grove). Planning permission was granted, provided

that new sewers were constructed and the ground level of Grasmere Grove was

raised up, to reduce the risk of the river Lostock flooding the new houses. By

1973, Haskell’s farm was no more and J. Haskell presumably retired on the

profits of the sale.

The farm buildings were all demolished when Grasmere Grove was built. Haskell’s is one of very few of the Whittle-le-Woods farms listed in Table One that has completely disappeared; while few others are still working farms, in most cases the farmhouses and outbuildings remain, generally as private houses (the main casualties, apart from Haskell's, are Old Crook and Darwen's, which were both on Dawson Lane). The survivors bear witness, as Haskell’s now cannot, to a once-thriving agricultural economy in this apparently inhospitable part of Lancashire. Meanwhile, the houses of Grasmere and Langdale Groves have been joined by many more as Whittle-le-Woods has slowly evolved from a village to a dormitory town.

Sources Used

Census returns

available at UK Census Online

1921 census available at Findmypast

Tithe maps

available at Lancashire Archive, Preston.

Historic

Ordnance Survey maps available at Old MapsGritt A (2016) The farming and domestoc economy of a Lancashire smallholder. In: Hoyle R (ed) The Farmer in England, 1650-1980. London: Routledge

Hodgkinson K (1991) Whittle & Clayton-le-Woods: A Pictorial Record of Bygone Days. Chorley: CKD Publications.

Winstanley M (1996) Industrialisation and the small farm: Family and household economy in 19th century Lancashire. Past and Present 152(1): 157-195