A House in Withnell

My son and his family recently moved into a house in Bury Lane, Withnell. It has everything a young professional family needs: four bedrooms, three bathrooms (one en-suite), fitted kitchen, car parking, etc, etc. But it was not always so, for their house is nearly 150 years old. In this article I will trace the early history of the house, in the context of the industrial history of Withnell township.

|

| The bottom of Bury Lane, Withnell |

Why is it there? – Withnell in the 19th Century

The ancient township of Withnell is a 3,000 acre slab of upland on the edge of the West Pennine moors. Prior to the 19th century it was almost exclusively livestock-rearing agricultural land, speckled with small, family-run farms, and little hamlets known as ‘folds’. There were no villages, no churches and no industry, other than some small-scale coal mining (of which more later), and quarrying. There was no manor house, or ‘Lord of the Manor’; the landowners lived elsewhere.

By the beginning of the 19th century, the Industrial Revolution, in the form of cotton textile production, had begun to impinge on Withnell. Handloom weaving became common in the farms and cottages, using cotton thread spun in the new factories established in neighbouring towns and villages. In 1799, bleaching and printing mills were built near to Brinscall Hall (just over the township border in Wheelton), and a row of cottages was built on School Lane in Brinscall, to house workers at the print and bleach works, along with more handloom weavers.

Communications to the township improved in the early 19th century. In 1801 the Sharples to Hoghton turnpike road was built through the east of the township (now part of the A675 Bolton-Belmont-Blackburn road). In 1819 the Leeds-Liverpool canal was opened, running through the western edge of the township near the river Lostock. Then in 1843, the Chorley to Finnington Bar road was upgraded to a turnpike (now the A674 Chorley-Wheelton-Blackburn road). Finally, in 1869, the Lancashire Union Railway was opened, running from St Helens through Wigan and Chorley to Blackburn, and passing along the valley that runs through the centre of Withnell township. Stations were built, named Brinscall, sited next to School Lane, and Withnell, placed where the line crossed the modern A675. The scene was set for the expansion of industry into Withnell township.

The industrialisation of Withnell was largely due to members of the Parke family. John Parke, a Preston cotton manufacturer, had two sons, Robert and John junior. In the late 1830s, these two separately bought land in Withnell, and set up cotton spinning and weaving mills. In 1839, Robert opened Withnell Mill, at the bottom of Bury Lane, and in 1840, John junior opened Abbey Mill (so named because the land once belonged to Whalley Abbey), a mile to the east on the Sharples to Hoghton turnpike. At the same time, they built themselves adjacent country houses in their adopted township: Withnell Hall (Robert) and Ollerton Hall (John). In 1843, Robert’s son Thomas Blinkhorn Parke, aged only 19, founded Withnell Fold paper mill, on land adjacent to the Leeds-Liverpool canal, and subsequently built his own mansion, Withnell Fold House, near to the mill.

Robert Parke died in 1855, and Withnell Hall came into the possession of a John Parkinson Parke. It is not clear what his relationship was to the rest of the Parke family. In 1841, aged 30 he was living with his young family in modest Edge End farm, near Abbey Mill and was a cotton spinner. By 1851, he had moved to Withnell House, off Bury Lane and was a cotton manufacturer owning two factories, though not in Withnell. By 1871, now ensconced in Withnell Hall, he was a manufacturer and “Lord of the Manor of Wheelton and Withnell”. In the 1870s, his son Frederick set up Withnell Brick and Tile Works, by the new railway line next to Withnell Mill.

Robert’s brother John was succeeded at Ollerton Hall by his sons, John and William (who never married, and lived there with their unmarried sister for the rest of their lives), and the firm of John Parke and Sons continued to own Abbey Mill through the rest of the 19th century.

Around the same time, Liverpool Corporation constructed a series of reservoirs in the east of the township, and a waterway, known as the Goit flowed along the valley, past Withnell Mill and Brinscall Bleach and Print works and joined with Anglezarke and Rivington reservoirs, eventually supplying Liverpool with fresh water. Withnell (or Brinscall) quarry was expanded on the lower western slopes of Great Hill. The growing population meant that agriculture remained important, and several new farms were built in Withnell in the first half of the 19th century.

All that industry required workers, and those workers required housing. Communities grew around Abbey Mill and Withnell Fold paper works, effectively becoming self-contained villages. Brinscall also became a village in its own right and housing extended along the newly-built Railway Road between Brinscall and Withnell Mill, and around the mill itself. Mount Pleasant, a rather ironically-named street of spartan two-up two-down terraced houses, was built in the late 1830s for workers at Withnell Mill, and more houses were built at the bottom of Bury Lane. Amenities were provided: shops, schools and churches, sometimes with financial support from the Parke family. The Parkes were staunch Methodists, explaining why there were rather more Wesleyan chapels in Withnell than pubs!

In the middle of the century, the ‘cotton famine’ triggered by the American Civil War caused a recession in Lancashire’s textile industry. Withnell Mill fell on hard times, and may have closed for some years. The economy picked up again, and in the 1870s, it was acquired by two young entrepreneurs from the south of England: Essex-born David Marriage and Harris Pinnock, from the Isle of Wight. The firm of Marriage and Pinnock prospered, and the mill went through several phases of expansion in the latter years of the 19th century. By 1891 it contained 30.000 spindles (for spinning thread) and 600 looms (for weaving cloth), manufacturing ‘Indian shirtings’ for export to the sub-continent. More workers were required, and more housing, leading to the development of Bury Lane, up the hill from the mill and towards St Paul’s church.

Bury Lane is Developed

The houses of Bury Lane are built on the site of the former Withnell colliery, whose shafts peppered the hillside overlooking Withnell Mill. The colliery was defunct by 1840, and probably long before. It is likely to have consisted of a scatter of short shafts dug more or less horizontally into the hillside. The clay underlying the coal was exploited later as the raw material for the Withnell Brick and Tile works, at the foot of the hill.

A long terrace of houses, was built up the left-hand side of Bury Lane (as you look up from the valley towards St Paul’s Church) in the 1870s. The terrace was originally named East View. The houses were built of brick, with stone facings, and were of a design known as ‘parlour houses’. They were a little larger than the houses in Mount Pleasant, with a short front garden, and a square back yard, which could be accessed from a lane running behind the terrace. The yard was effectively the ‘utility room’ of the house, and included the coal store, the ash pit (refuse dump) and the 'long drop' privy - in the days before water closets became standard, you wouldn’t have wanted the lavatory to be inside the house. Then there was a scullery in an extension at the rear of the house. In some of the houses, the extension was single-storey, and the houses had two bedrooms, while others, including my son’s, had two-storey extensions, with a third bedroom above the scullery. This simple addition made a big difference to the living space. The front downstairs room was known as the parlour, with the best furniture and heirlooms, and behind it was the kitchen, with a range for cooking. The family would spend most of its time in this room. The scullery would have a sink and would have been used for food preparation and storage, and washing clothes. Large families had to be creative with where they slept and there would not of course have been a bathroom. Behind the houses were green fields, belonging to the ancient Withnell Farm, which still stands close to the terrace yards.

In the 1890s a similar row of terraced houses was built on the opposite side of Bury Lane, blocking the view from the original terrace. The ‘East View’ name was dropped and the whole of Bury Lane was renumbered. It is almost certain that this numbering system has not been altered since, allowing us to identify who was living in my son’s house in the early years of the 20th century.

John Heyes and his Family

John Heyes was born in 1854 in the small cotton town of Great Harwood, about ten miles north of Withnell, between Blackburn and Accrington. His father, also John, had been born in the town, and was a weaver in one of its eight cotton mills. His mother Jane had been born in the neighbouring town of Rishton. John was the second eldest of eight children. By 1871, John, now aged 17, had joined his father and sister Mary as a weaver in a Great Harwood mill.

By 1881, John’s family circumstances had changed drastically. Sometime in the early 1870s, the family had moved to Withnell, perhaps tempted by the new opportunities afforded by the reopening of Withnell Mill. But during the decade, both his parents died (in their early fifties), and by 1881 John, aged 27, was living in a cottage near St Paul’s church with his four youngest siblings. He was working as a weaver in Withnell Mill, as were his sister Jane, aged 18, and his brother David, 14. Two further brothers, Thomas and James, were still attending the school at the foot of Bury Lane.

In 1882 John married 24 year old Mary Jervis, who lived with her widowed mother Margaret and five siblings in a cottage on Mount Pleasant. She had been born in Wrightington, between Chorley and Wigan; her late father Thomas had been a quarryman. By 1891, John and Mary were living down the road from Mary’s mother on Mount Pleasant. They had quickly acquired three children (a fourth died in infancy): Herbert, Margaret and Thomas. Also living with them, in a two-bedroom house, was John’s brother Thomas, now 21 and working in a grocers shop.

By 1901, John and his family had moved to Bury Lane. John had by now given up weaving, and was employed as a warehouseman at the mill. His older children, Herbert (17) and Margaret (16) were now working as weavers, supplementing the family income and allowing the luxury of renting a three-bedroom house. The family was still living there in 1911. John, now 57, was a labourer at the mill. Herbert had left home, and was a police constable in Blackburn, but younger son Thomas, now 21, was still there, inevitably working as a weaver. Also taking advantage of the three-bedroom house was John and Mary’s daughter Mary, now 26 and married to a quarryman, William Rossall. It was still a crowded household, as Mary and William had a son, 11 month-old John.

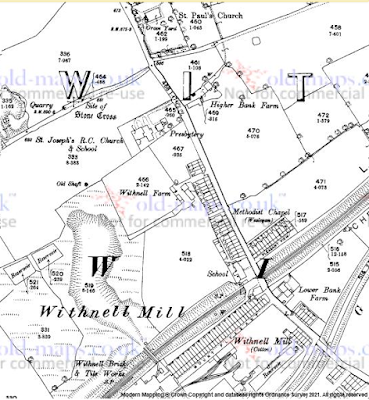

The Bury Lane area, as depicted on the 1:2500 Ordnance Survey map of 1894. The terraces on the eastern side of the road had not yet been built. Pertinent to the Heyes family are: Withnell Mill, where most of them worked; St Paul’s Church, where the family lived in a cottage when they first moved to Withnell, and Mount Pleasant (between the mill and the railway), where Mary had lived with her mother, and John and Mary lived prior to moving to Bury Lane.

The Heyes family were by no means unusual. It was common at a time when virtually all houses were privately rented for working class families to move frequently as their circumstances changed. It was also of course usual for people to live near their workplaces. Villages like Withnell must have had a campus-like atmosphere, where everyone worked with, or knew, everyone else. Crowded houses were also depressingly common. In 1911, the Heyes’s neighbours were Herbert and Margaret Gill, printer’s labourer and weaver, with their three school-age children, also Margaret’s mother and niece, and in the two-bedroom house on the other side, Joseph Snape, a widowed cotton mill labourer and his seven children, aged from 23 to 7. We tend to think of overcrowding, multi-generational households and pressing landlords as being 19th century problems, but the current pandemic has shown that such issues are highly pertinent in deprived former industrial areas today.

By 1921, John & Mary's son-in-law William Rossall had become a dairy farmer, at Higher Hill Farm, Tockholes, and had moved there with his wife Mary, their six children - and John and Mary Heyes, now retired. The house in Bury Lane was still in the family however, now occupied by Mary Heyes's younger brother Thomas Jervis, an Overlooker at Withnell Mill, and his wife Ellen. They had no children, and their thus spacious three bedroom home was a reward for Thomas's ascent to middle management!

The Twentieth Century and Beyond

The house will have undergone many improvements since the time of the Heyes family, but they are difficult to date. It will have gained hot and cold running water, a water closet, a dustbin (to replace the ashpit), a bathroom (and later two further bathrooms), electricity, gas, telephone, television, fitted kitchen, central heating, double glazing and the internet. The coal fires that previously heated the rooms and the range that cooked the occupants’ food were removed in the name of progress. By 1930 the scullery had been extended sideways to the full width of the house, creating a rear kitchen and two ‘reception rooms’ and at a later date a loft extension was carried out to form a fourth bedroom and en-suite bathroom. The front garden was paved over to create a much-needed car port. What had been, in the late nineteenth century, a comfortable family residence is still that today.

Withnell township has also gone through many changes. Its days as a centre for industry are long gone. The brick and tile works soon exhausted the local clay, and by 1912 the firm had moved to a new site at Stanworth, east of Abbey Village, where it continued to operate until at least the 1970s. Withnell Fold Paper Mill was sold to the national firm of Wiggins Teape, and continued to operate until 1967. Withnell quarry is still operational, cutting away more and more of the hillside to the south of the village, though today the stone is used as aggregate for road construction rather than ashlar for housing.

The Lancashire cotton industry suffered increasingly from foreign completion in the early 20th century, and the local mills were dealt a devastating blow by the 1929 Wall Street Crash and subsequent recession. Withnell Mill and Brinscall Bleach and Print Works both closed down in 1930, causing major hardship in the local community. Abbey Mill hung on until the 1960s, when it too closed, along with much of the remaining cotton industry in Lancashire. In 1960, Withnell lost its railway, with the closure of the Chorley – Blackburn line.

The Parke family has also departed from Withnell. Following the death of William Parke of Olleton Hall, the estate was bought by Herbert Parke of Withnell Fold, son of Thomas Blinkhorn Parke, who had already acquired the Withnell Hall estate from J Parkinson Parke (hope you’re keeping up!) The estate remained in his family until the 1950s. Today, Ollerton Hall is still a private house. Withnell Hall was converted in the early 20th century into a pulmonary hospital, and subsequently a care home, and is now the centre of an exclusive housing estate. Withnell House, once the residence of J Parkinson Parke, is now a private rehab and detox clinic, and Withnell Fold House is another care home.

So this brings the story of Withnell and my son’s house in Bury Lane up to date. Onwards to the next 150 years!

Source Used

Census returns available at UK Census Online

1921 census available at Findmypast

Historic Ordnance Survey maps available at Old Maps

Clayton D (2011) Lost Farms of Brinscall Moors. Lancaster: Palatine Books

Martin N (1993) Deadly Dwellings: The Shocking Story of Housing and Public Health in a Lancashire Cotton Town. Preston: Mullion Books